Gunpowder flask with figures in Portuguese dress, EA1983.243 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Gunpowder flask with figures in Portuguese dress, EA1983.243 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

This lacquered wood gunpowder flask (kayaku-ire) was produced in Japan. It is artistic in form but with an important practical use. The flask gives a useful insight into a fascinating period of Japanese history and reflects the history of contact between Europe (especially Portugal) and Japan. It depicts Portuguese figures, in exaggerated poses, on the front and back panels of the flask. The two flat lacquered panels are affixed to a wooden body, rounded at the sides and bottom. It is an example of an artistic style known as Nanban, which developed during this period of initial European contact (1543‒1639), although it is possible the object was produced later than this date. Apart from the wood and lacquer, it also includes copper, which was used to make the spout and side pin (likely for attachment to a belt or equivalent). It was acquired by the museum in 1983, purchased at auction with the help of the Friends of the Ashmolean.

Historical Background

The period of initial European contact with Japan coincided with what the Japanese call the Sengoku jidai, ‘the Age of Warring States’. This was a protracted period of civil strife lasting almost one hundred and fifty years up to around the early 1600s. Japan at this time, although ruled nominally by an Emperor who commanded the loyalty of the nobility, was in practice ruled by a shogun, a powerful lord who was the supreme commander of the armed forces and acted as a head of government in whom most practical power rested. The Japanese term for the shogun’s government (shogunate) was bakufu, which literally means ‘tent-government’ and came to refer to the host of bureaucrats and court officials who worked under the shogun. The sixteenth century in Japan was characterized by the instability resulting from the collapse of one shogunate and the rise of another. This gunpowder flask was produced around 1600, when the warlord Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) was establishing his rule, beginning the era of the Tokugawa shogunate (1615–1868). This period is also known as the Edo period, as the new government was based in the city of Edo (modern Tokyo), as opposed to Kyoto, the former capital where the emperor still lived. The period saw the initial contact between Japan and Europeans, the Portuguese having come upon Japan in the 1540s. As their arrival coincided with this period of conflict and upheaval, the Portuguese were able to initiate trade with the Japanese, as well as engage in Christianization, courting provincial rulers (daimyō) and even negotiating control of Nagasaki in the 1580s, although this was short-lived.

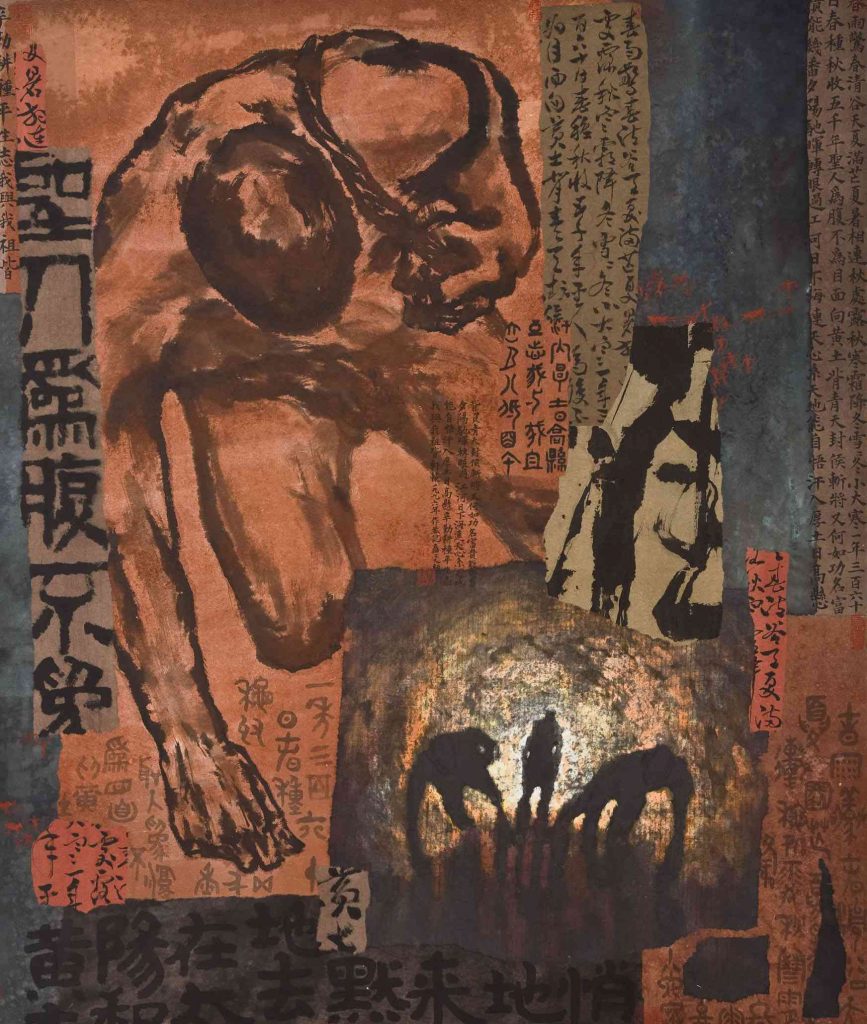

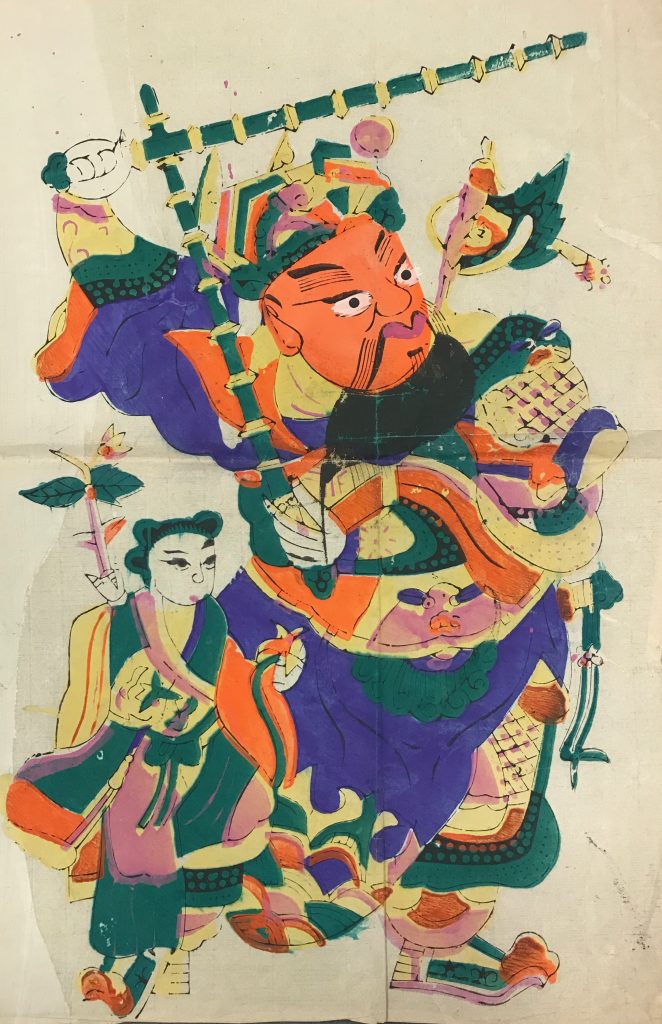

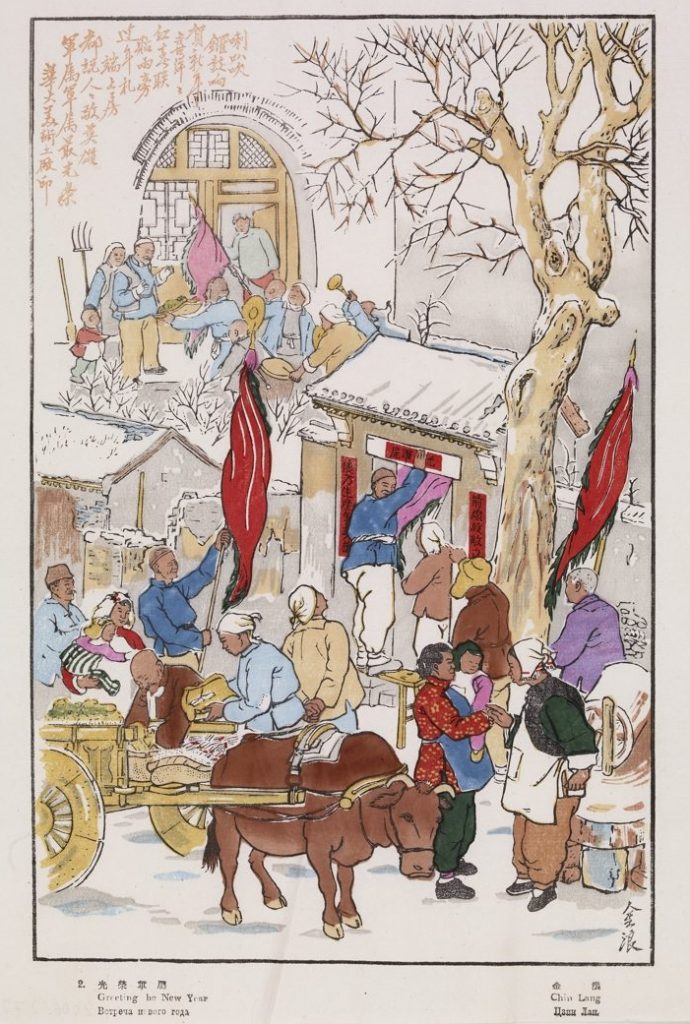

Nanban panel attributed to Kano Naizen, Image: © National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon, Wikimedia Commons

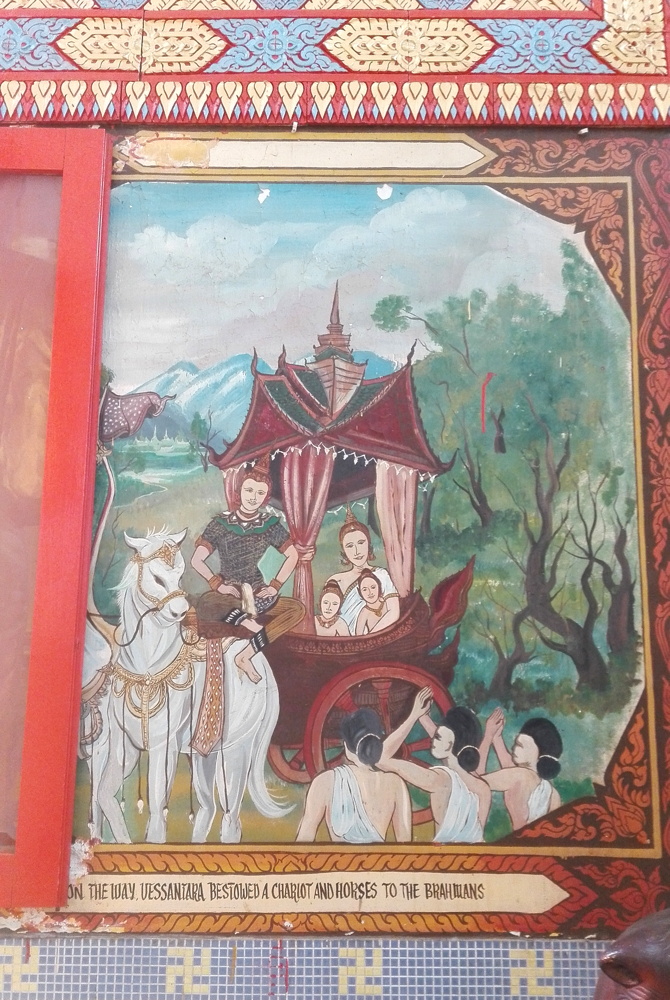

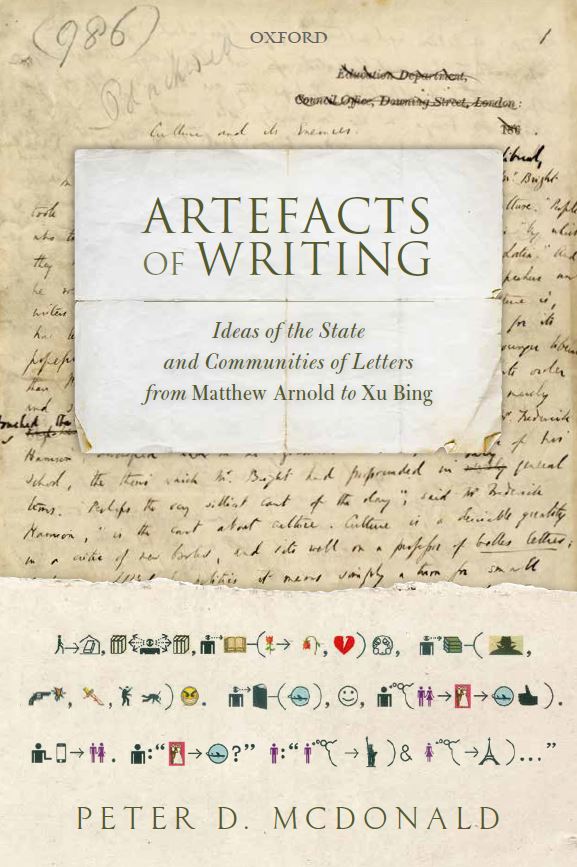

Besides the significant social and cultural exchanges that followed the Portuguese arrival in Japan, there was also a marked economic interaction. The Portuguese were enthusiastic for Japanese goods such as porcelain (and there was also a significant trade in Japanese slaves) but there was very little in the way of European items imported into Japan. The Europeans’ main contribution was to act as middle men for other Asian goods such as silk from China. The main exception to this rule was the trade in gunpowder weapons: specifically the European matchlock heavy arquebus, known as the musket. The general term for gunpowder weapons in Japan was Tanegashima, after the island where they were said to have been first introduced, but other names included hinawajū, ‘fire-rope gun’, and teppō, ‘iron cannon’ or ‘metal gun’. Teppō would subsequently become the standard term. Although the Chinese had pioneered the use of gunpowder technology, the matchlock, the first firearm with a trigger, was a European innovation which was introduced to Asia (India and likely also China) through the Ottoman Turks. However, the first documented trade of firearms in Japan was conducted by the Portuguese in 1543, when a Chinese pirate/trader vessel with several Portuguese on board was shipwrecked near Tanegashima and the local daimyō was much taken with the weapons and purchased them for a huge sum. Print designer Katushika Hokusai (1760–1849) imagines the incident in the work below.

‘First Guns in Japan’, Katsushika Hokusai, 1817, Image: © Noel Perrin Giving Up the Gun, Wikimedia Commons

Firearms were transported to Japan from the Portuguese bases in Goa and Malacca, where armouries and workshops were able to produce these guns in significant numbers. By the 1560s gunpowder weapons were being used in large numbers in Japanese battles by Japanese foot soldiers (ashigaru). Their advantages and drawbacks in Japanese warfare were much the same as with European. They were dangerous to the user, inaccurate, slow to load and reload, and could be very unreliable in wet weather. Conversely, they were easy to manufacture, easy to use (meaning people of low status and no military background could be instructed in their use) and had superior penetrative power compared to other missile weapons like bows. Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582), a successful military leader of this period, recognised the potential of muskets early on and won repeated successes using large numbers of musket-wielding troops, most famously at the Battle of Nagashino in 1575.

Purpose

The flask under discussion is a gunpowder flask, used in the loading of matchlock guns. To fire the weapon, one pulls a lever or trigger attached to the bottom of the weapon. The action of pulling the trigger moves a second lever, causing a match (burning cord) to be lowered into the flash pan where the priming powder sits. The flash from the lit priming powder moves through the vent and ignites the main powder charge in the gun barrel. This reaction expels the projectile down the barrel and out of the muzzle. The powder flask is used to accurately apply a measure of powder to the weapon via the narrow spout. As the smaller amount of priming powder had to be of finer quality, typically the user would have two flasks, one with priming powder, and one with coarser powder used as the main charge. The most efficient way to use the flask was to prepare cartridges containing the right amount of powder before battle so one did not have to fumble around with multiple flasks in the middle of an engagement.

Production and Design

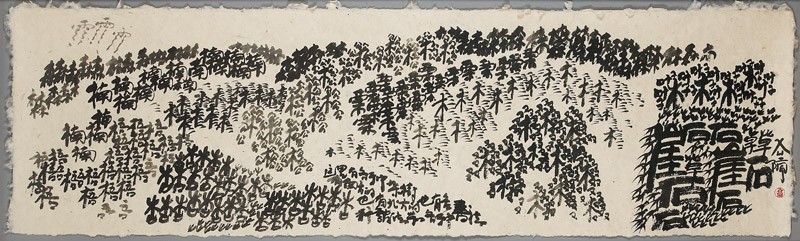

To make Japanese lacquerware, objects are covered with the treated sap of the lacquer tree or sumac. The objects can be of any material: wood, paper, leather, textiles and ceramics. Wood was the preferred medium for Japanese artisans.

Lacquer Tree, Toxicodendron vernicifluum, formerly, Rhus verniciflua. It is indigenous to China but has been found across East Asia since ancient times, Image: © Takami Torao, 15 August 2009, all rights released, Wikimedia Commons

In Japan the tree is called urushi, a name from which the name of the oily allergenic compound urushiol comes. Urushiol, contained in the tree’s sap, is toxic but vital in the production of the distinctively hard-wearing East Asian lacquer. The tree bark is cut and the sap collected: the sap is an almost clear liquid which releases a poisonous vapour and is then refined by sieving and evaporating to reduce the water content from around 30% to 3%, by which time it is more viscous and completely colourless. This process must be performed in a dust-free environment with very high relative humidity. Pigmentation can be achieved by adding dyes, metallic oxides, ash or cinnabar.[1]

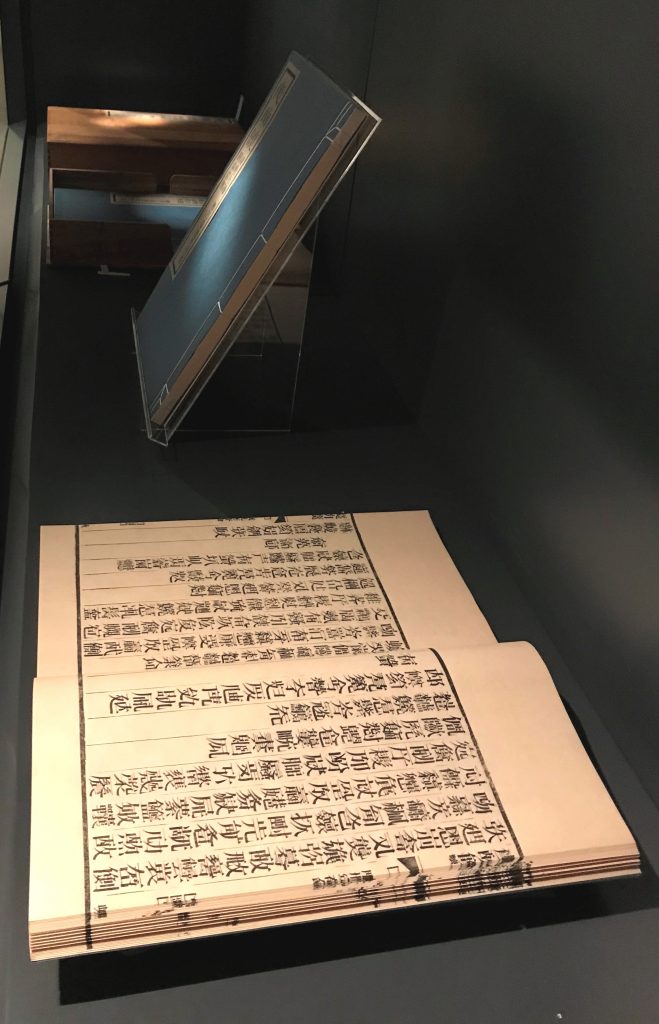

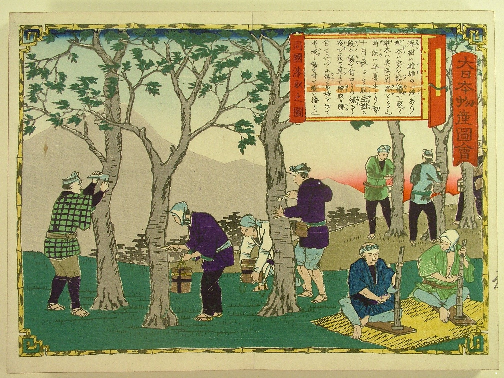

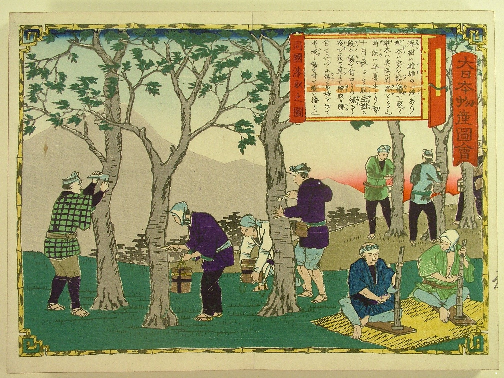

‘Harvesting lacquer in Mikawa province’, from the woodblock printed book Products and Industries of Japan (Dai Nippon Bussan Zue), 1877, by Utagawa Hiroshige III, EA1964.224. © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

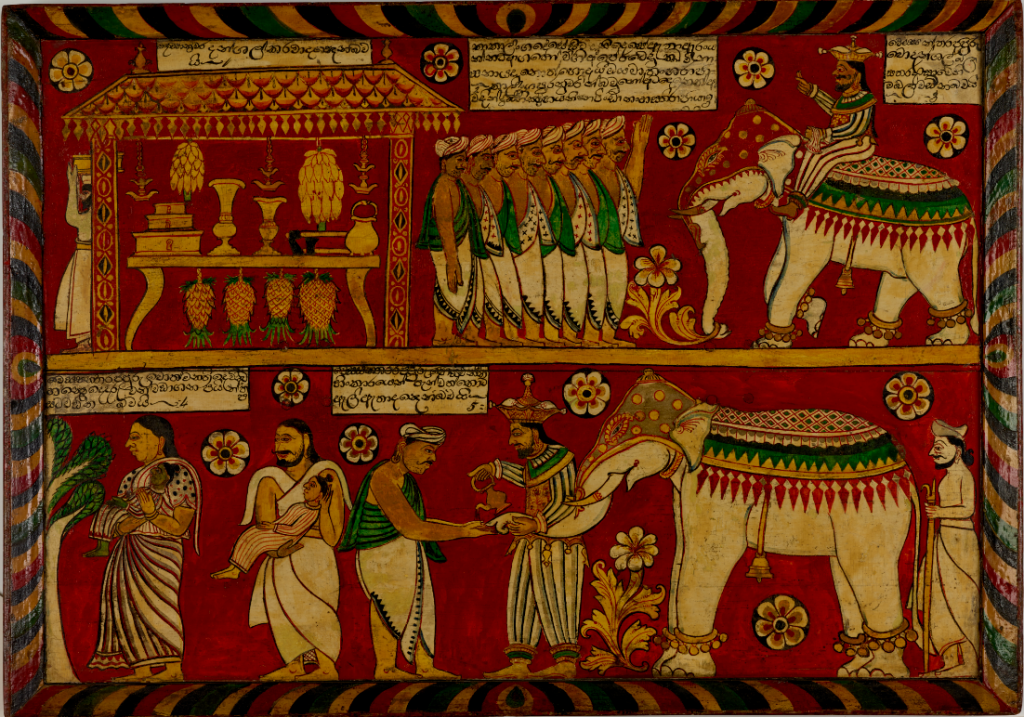

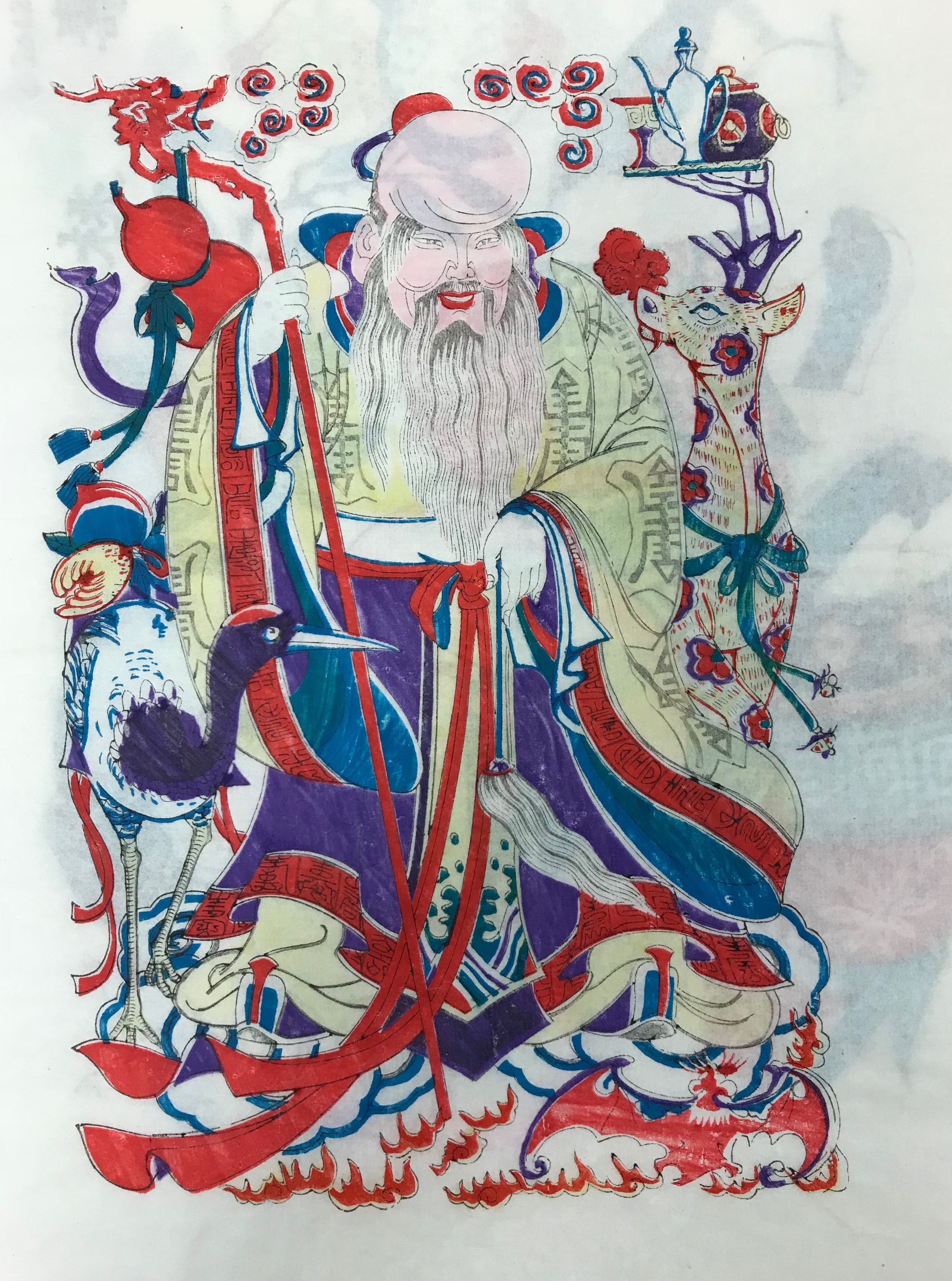

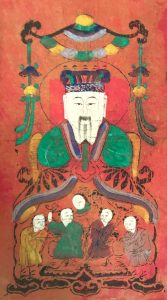

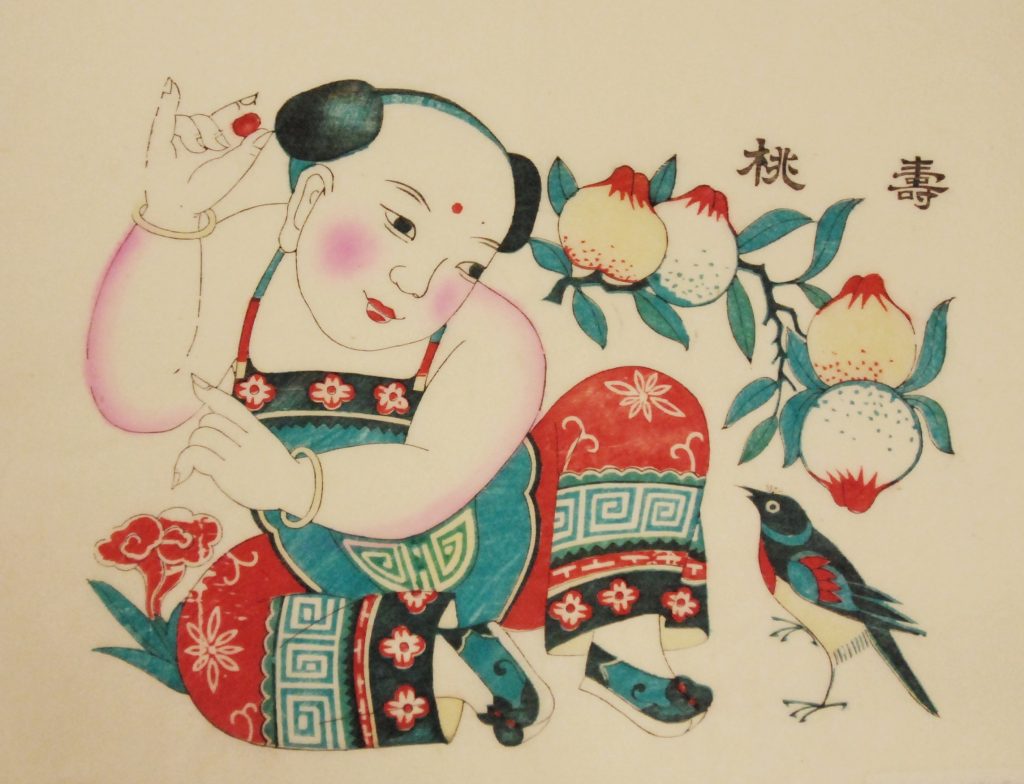

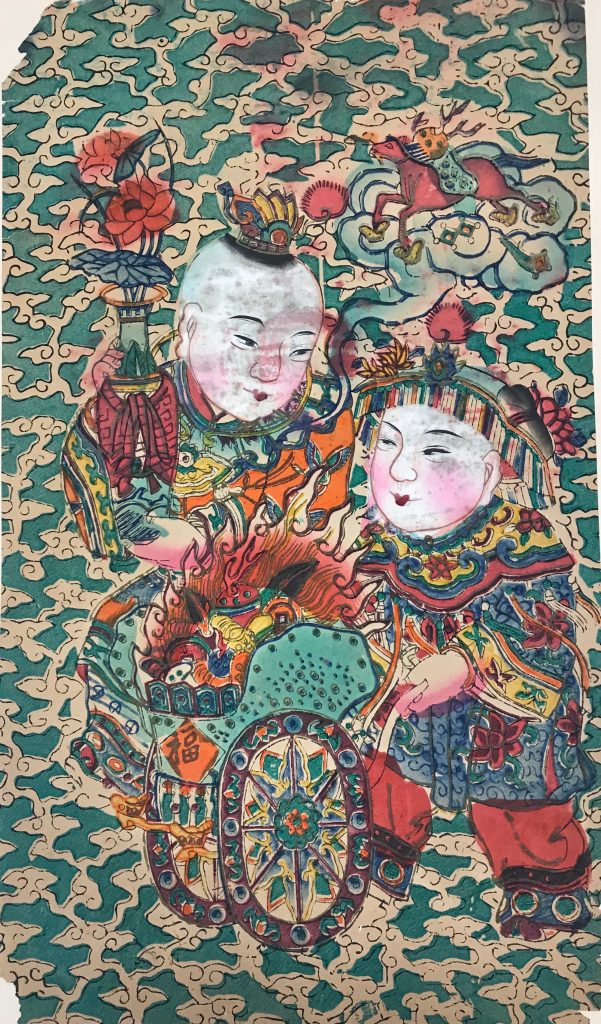

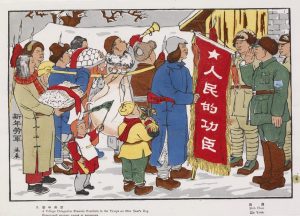

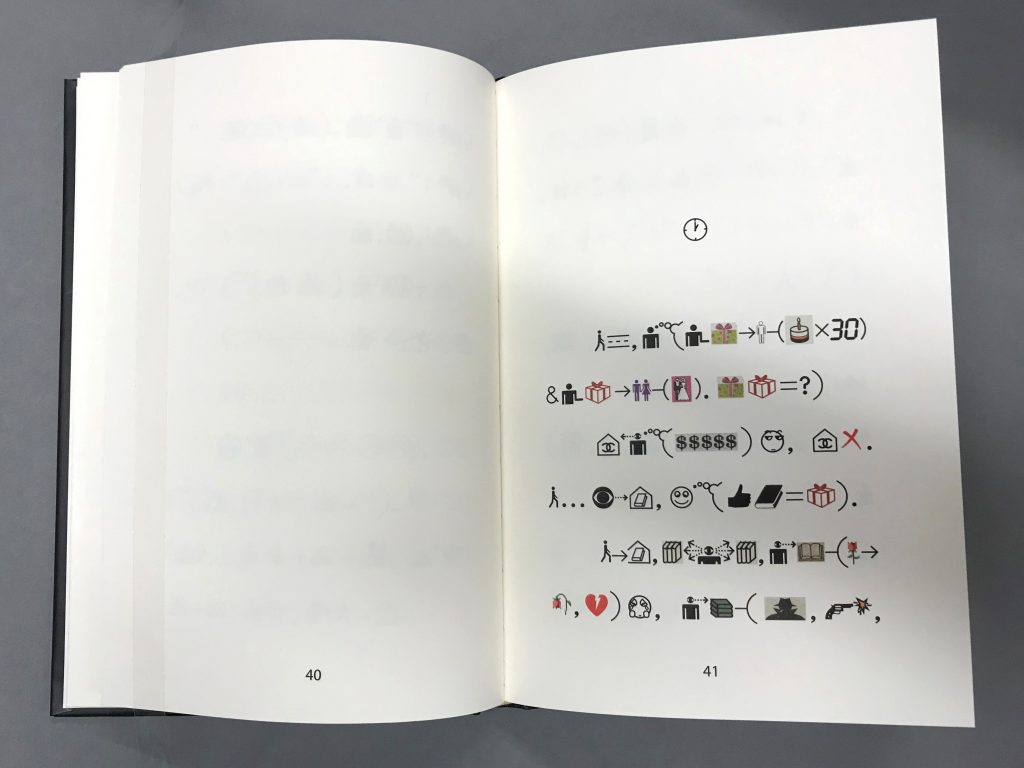

Japan already had a highly developed lacquerware tradition by the time of initial contact with Europeans, 1543‒1639. With the arrival of the musket, and foreign traders who prized Japanese lacquered objects for trade, the powder flask rapidly became a well-established item of lacquer production. As there was no surface treatment equivalent to lacquer in Europe, lacquered objects were prized for their quality, rarity and exotic character and therefore fetched very high prices in European markets. Objects that were produced for sale to Europeans, initially the Portuguese, were known as Nanban wares. Nanban, which translates as ‘Southern barbarian’, was the term used to refer to these early European visitors. Originally coming from Chinese, the term was used in China and Japan to refer to South Asian peoples, or any foreigner who was not Chinese, Japanese or Korean. However, by the sixteenth century in Japan it came to be used in reference to Europeans, specifically the Portuguese. The subsequent interactions between these two groups gave rise to the production of a distinctive type of art: Nanban art. Typically, Nanban-style objects comprised thick black lacquer, as seen on the side panels of the flask.

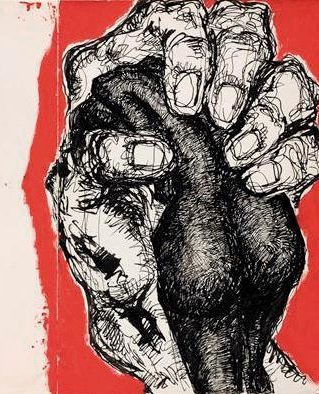

The figures on both the front and back of the flask wear the distinctive bombacha trousers worn by the Portuguese in the East, which were notable to the Japanese eye. Both the clothes and poses of the figures seem to be exaggerated for humorous effect. This light-hearted depiction of foreigners suggests that this item may have been made for the domestic market, a theory supported by the fact that the likely date of production of the flask is after the expulsion of the Portuguese from Japan in 1639. Beyond the obvious association between the Europeans and the firearms they introduced, there is no clear connection between the figures on the object and the purpose of the flask.

Historical epilogue

The Portuguese were not able to monopolize contact with Japan for long, as other European powers – the Spanish, Dutch and English – were keen to muscle in on the lucrative opportunities in the Indian Ocean and the Far East. With the end of civil war, and the restoration of a strong central government in Japan in the early 1600s, the Japanese authorities clamped down on the presence of foreigners in the country. This policy came to be called sakoku (‘closed country’ or ‘national isolation’), following an edict of 1635. It has traditionally been thought to have been due to a desire to minimize foreign influences, whether political religious or economic, but recent scholarship has also highlighted that this was part of the centralizing agenda of the Bakufu: being part of a range of policies aimed at limiting the power of the local lords (daimyō). In any case, of the four European powers involved in Japan, the English left first, in 1623, voluntarily because they were not profiting from their trading post in Hirado. Subsequently the Spanish were expelled from Nagasaki in 1624, and likewise the Portuguese in 1638 because of continued illicit missionary work which the Japanese government had forbidden. Only the Dutch were left.

The Japanese had a different term for the Dutch: kōmō, meaning ‘red hair’, more to suggest a demonic nature than to describe the actual colour of all the Dutch visitors’ hair. Although the Dutch had shown no desire to interfere politically or religiously in Japan, and were only interested in trade, they were limited to occupying a tiny artificial island in Nagasaki harbour called Deshima (next to a slightly larger island reserved for the Chinese). For the next two centuries or so, it was the Dutch who monopolized the European trade of Japanese goods. This tiny outpost also allowed the Japanese to retain a tenuous connection with the West and to enable transmission of Western technology: see the term Rangaku (literally: ‘Dutch learning’).

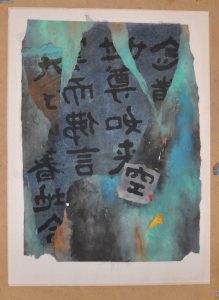

‘Dish with Dutch East India Company monogram’, EA1994.103 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

This porcelain plate of the late seventeenth century bears the emblem of the Dutch East India Company in the centre (VOC, for Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie). It is an example of Japanese export porcelain, a valuable trade commodity which the Dutch were the only Europeans legally entitled to export to Europe. The plate is currently on display in the Ashmolean’s ‘West Meets East’ gallery (Gallery 35).

- Ben Skarratt, UEP Museum Assistant, responsible for collections and object teaching support across the Ashmolean’s Eastern Art, Western Art and Antiquities departments.

[1] Process description taken from Japanese Export Lacquer 1580-1850, Impey and Jörg, Hotei Publishing, Amsterdam, 2005, p. 75

Bibliography

Japanese Export Lacquer 1580-1850, Impey and Jörg, Hotei Publishing, Amsterdam, 2005

Giving Up The Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1543-1879, Noel Perrin, Godine, New Hampshire, 1979

The Namban Art of Japan, Yoshitomo Okamoto, translated by Ronald K Jones, Weatherhill/Heibonsha, New York & Tokyo, 1972

Lacquer: technology and conservation: a comprehensive guide to the technology and conservation of Asian and European lacquer, Marianne Webb, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 2000