The theme of the third and final blog post in the series complementing the exhibition “A Century of Women in Chinese Art”, on show at the Ashmolean Museum until the 14th of October 2018 is women and martial arts.

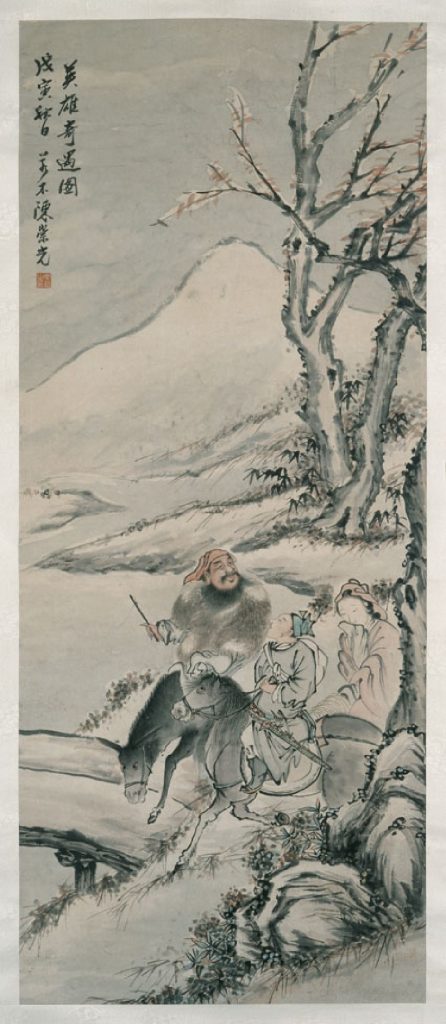

First we will look at a hanging scroll that appears in the exhibition by Chen Chongguang 陳崇光 (1839-1896). This shows three characters from Qiuranke zhuan虯髯客 (The Legend of Qiuranke), a work of popular fiction written by the Daoist priest Du Guangting 杜光庭 (850-933) in the latter part of the Tang dynasty.

Chen Chongguang ,The Hero’s Happy Encounter, 1989, EA1966.85 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

In this painting, entitled: Yingxiong qiyu tu英雄奇遇圖 (A Remarkable Meeting of Heroes) (1878) the eponymous hero Qiuranke 虯髯客 (Knight with the Dragon Beard) can be seen on the left. After meeting Hong Fu Nü 紅拂女 (Lady of Red Fly-Whisk) (right) and her husband Li Jing 李靖 (centre), together, as the “Three Heroes of the Wind and Dust”, they strove to overthrow the Sui dynasty in order to establish the Tang.

In the story, before the scene depicted in the painting takes place, Hong Fu Nü eloped with Li Jing, escaping from the court of the powerful general Yang Su楊素 (d. 606) where she had been working as a courtesan. Despite her demure appearance as seen in this painting, she is said to have excelled at martial arts and indeed The Legend of Qiuranke, in which she appears so prominently, is often referred to as the earliest Wuxia 武俠 (Martial Arts) novel.

Famously, a poem about Hong Fu Nü can be found in the Qing dynasty novel of manners Honglou meng 紅樓夢 (The Dream of the Red Chamber) in which one of the central characters, Lin Daiyu 林黛玉, is humorously compared to her. The poem takes Hong Fu Nü’s elopement with Li Jing as its theme:

Bowing with hands clasped, the hero’s manner inimitable,

The beauty, with great vision, saw the dead end that lay ahead.

In that moribund place Lord Yang would meet his end,

How could he hope to rein in a heroic woman such as she?

The story of the three heroes became the inspiration for a number of related literary works, and, as with so many traditional stories in China, has recently been made into a television drama series – an historical love story – “Hong Fu Nü of the Three Heroes of the Wind and Dust” (Fengchen sanxia zhi Hong Fu Nü 風塵三俠之紅拂女) (2004), starring the popular actress Shu Qi舒淇. In this, it is she and her fellow Tang court ladies who take centre stage, all of whom excel at performing the most unlikely of airborne, acrobatic, martial arts moves.

Dish with figures from the novel The Water Margin, 1680 – 1720, Mallett bequest 1947, EAX.3531 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

It will be remembered from the previous instalment that amongst the 108 “brothers” in the Ming dynasty novel, the Water Margin a handful are women and as with all other heroes in the story they excel at martial arts. There a number of ceramic examples in the Ashmolean collection decorated with figures from the Water Margin, each showing three heroes carrying distinctive weapons in a variety of martial arts stances.

In this example can be seen, from right to left: Zhang Qing 張清 “The Featherless Arrow”; Yang Zhi 楊志 “The Blue-Faced Beast”; and Suo Chao 索超 “The Impatient Vanguard”, all three carrying weapons as if ready to engage in battle. Suo Chao wields the Guandao關刀 (a weapon named after the Chinese god of war, Guan Yu 關羽), Yang Zhi has a sword sheathed on his belt and in addition, grasps in his hand a variation of the weapon known as the Monk’s Spade, and Yang Qing appears to carry a pot and a ball, no doubt also to be used as weapons.

Porcelain painted in enamel colours, ca. 1700, Salting bequest, C.1196-1910 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A similar example in the Victoria and Albert Museum again shows Yang Zhi, this time together with Xie Zhen 解珍and one of the three female heroes from the novel, Gu Dasao 顧大嫂 “The Tigress” (Mu da chong 母大蟲), as introduced in the last instalment of the blog. In the scene depicted on this plate Yang Zhi and Gu Dasao have been battling with Xie Zhen and have apparently succeeded in disarming him. Yang Zhi holds a trident-like spear and Gu Dasao the sword known in Chinese as the baojian 寶劍 (Precious Sword).

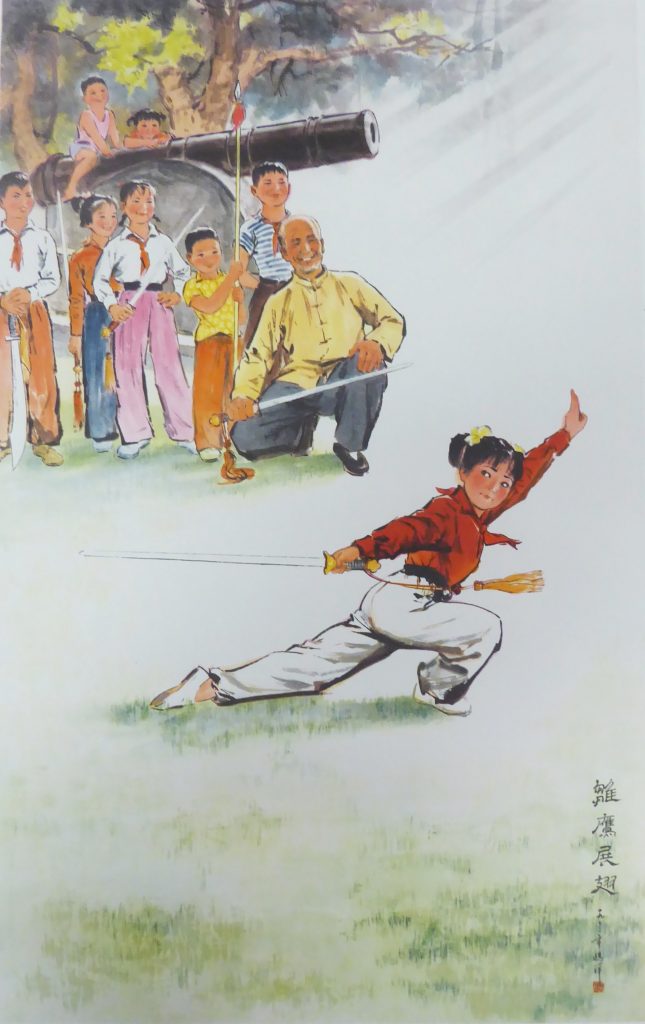

By the second half of twentieth century martial arts had become firmly established as a national sport in China, having been formalised in the decades immediately prior to this. In a 1974 Cultural Revolution propaganda poster in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, a young girl demonstrates her skill with the baojian in front of her classmates, with their master looking on in approval. The poster is a reproduction of a painting by the artist Ou Yang 鸥洋 (b. 1937) entitled Chuying zhanchi雏鹰展翅 (The Fledgling Eagle Spreads its Wings). The painting, showing members of the youth organisation, the Shaoxiandui 少先队 (Young Pioneers), promotes the future role these young people might go on to play in the defence of the Mother Country, as suggested by the martial theme and the large cannon seen in the background.

The Fledgling Eagle Spreads its Wings. Poster (1974), EA2006.208 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

More examples of girls practicing with a baojian can be seen in a set of souvenir matchboxes showing a variety of different postures. These postures, all standard forms learned in martial arts practice, are not named, the writing on the reverse of each matchbox simply listing basic instructions on how to use matches.

Four matchboxes with small girls practicing martial arts EA2010.95

For an excellent example of sword technique and the postures as practiced in one style of martial arts we can see the extraordinary skill of Chen Suijin in the 1st Taolu World Cup – first place in Women’s Taijijian (Taiji sword).

A stylised form of swordplay is also central to martial roles played in Peking Opera and one of the most famous of these is the sword dance performed by Yu Ji in Bawang bieji 霸王別姬 (Farewell my Concubine), the story of Xiang Yu 項羽, King of Chu, and his concubine Yu Ji 虞姬. In recent times this was made famous by Chen Kaige’s film Farewell my Concubine (1993). Earlier in the century, though, the double-sword dance towards the end of the opera was made a speciality of the great male performer of female roles Mei Lanfang. Following the sword dance Yu Ji snatches Xiang Yu’s sword with which she commits suicide.

Another martial role played by a woman is Mu Guiying 穆桂英 from the Peking Opera Yangjia jiang 楊家將 (Generals of The Yang Family), a staple of the Peking Opera repertoire, in which the female members of the family are prominent in their exhibition of martial prowess.

Song Guangxun 宋广训 (b. 1930, Baxian, Hebei) from The Generals of the Yang Family, Mu Guiying in a Beijing opera, 1978 (design), 2006 (print), EA2007.48 © The artist

An inkstick with impressed decoration, showing a baojian and a set of Chinese books, is dated the eighth year of the Xianfeng reign (1858) and is made in a traditional form that stretches back centuries. Such inksticks were ground with water on an inkstone to produce the pigment that was applied with a brush in both traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy practice. This example was made by the Hu Kaiwen, an ink factory established in 1765.

Ink stick with decoration showing a book and sword, Hu Kaiwen Ink Factory, EAX.5521 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The decorative motif found on this inkstick refers obliquely to one of the group of semi-mythological figures known as the Baxian 八仙 (Eight Immortals). This is in fact an example of one of the An Baxian 暗八仙 (Hidden Eight Immortals). In such imagery, the Eight Immortals do not appear in person but are substituted by the specific attributes with which they are associated, in the case of Lü Dongbin, as shown on the inkstick, these are the baojian and a set of books. A mythical figure associated with both scholarly pursuits and martial arts Lü Dongbin 呂洞賓 is said to have been the founder of the internal martial arts style known as Baxian jian 八仙劍 (Eight Immortals Sword). The silk hanging below is one of a pair in the current Ashmolean exhibition and depicts the Eight Immortals with their attributes.

For more on the Eight Immortals please see my previous blog for the exhibition “Pure Land: Images of Immortals in Chinese Art” shown at the Ashmolean in Gallery 11 in 2016.

Embroidered Hanging (detail: Lü Dongbin) EA1958.83 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Despite what is often suggested by martial arts practitioners, it is most unlikely that a style of sword practice such as this could have been passed down through the centuries, and this example, as with most martial arts styles, no doubt developed into what we see today during more recent times; perhaps more specifically in the nineteenth century or the Republican period at the time when martial arts made a resurgence as a national sport.

The exhibition “A Century of Women in Chinese Art”, at the Ashmolean Museum closes on 14 October 2018.

Posted on behalf of Dr Paul Bevan, Christensen Fellow in Chinese Painting, Ashmolean Museum.