In the second instalment of this blog, complementing the exhibition “A Century of Women in Chinese Art” now on show at the Ashmolean Museum until the 14th of October 2018, we will look at examples in the museum’s collection of objects on Peking Opera themes.

These include two paintings by Gao Made 高馬得 (1919-2007); one by Guan Liang 関良 (1900-1986); a popular print from the beginning of the twentieth century showing a selection of heroes of the Water Margin (a common theme in Peking Opera); and a small group of matchboxes from the 1970s.

Three figures from the ballet version of Red Detachment of Women, 1970s, Gittings Gift, EA2008.36.c © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

In the previous instalment of the blog mention was made of the Red Detachment of Women. The most famous version of this story is the ballet version, based on a 1961 film of the same name. Following this came the Peking Opera version, which, to the fan of Peking Opera is equally impressive, if not quite so exciting for the lay viewer.

Peking Opera version of the Red Detachment of Women

Before going any further I feel it is important to say a word or two about the term “Peking Opera”. The type of sung drama to which this term refers is known in Chinese as jingju 京劇 (or sometimes jingxi 京戲), a term that might be best translated into English as “Drama of the Capital”. The term “Peking Opera” is not a translation of the Chinese term jingju but was devised by English speakers in the nineteenth century to refer to this specific dramatic form.

Peking Opera was, then, an English-language term used to refer to the Chinese art form known in Chinese as jingju and in much the same way that “Peking University” is still the official name of that university (i.e. it has not changed its name to “Beijing University”), it should be seen as more correct to use the term “Peking Opera” when referring to jingju; the term “Beijing Opera” being something of an anomaly, with the word “opera” used simply to refer to a form of sung drama.

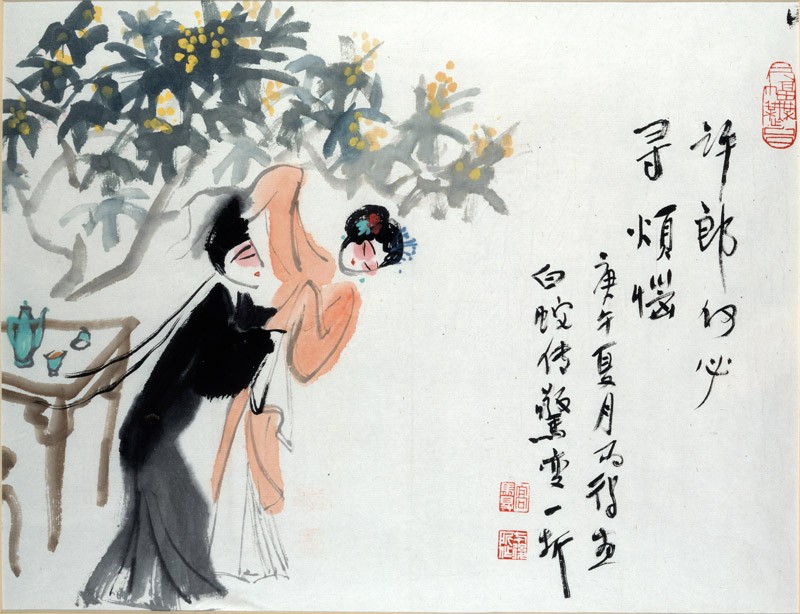

Gao Made, The Legend of the White Snake (Baishe zhuan 白蛇傳), 1990, Reyes Gift, EA1995.190 © the artist’s estate

Returning to the theme of Peking Opera as it appears in the Ashmolean exhibition. Gao Made’s interpretation of “Stunned by the Transformation” – a scene from The Legend of the White Snake (Baishe zhuan 白蛇傳) – is a good example of his work and is part of trend particularly prevalent after the foundation of the PRC to paint scenes from Peking Opera with a view to displaying one of China’s national treasures to the world. A similar promotion can be seen in the case of martial arts, the subject of the next instalment of this blog.

Gao Made is a largely self-taught painter and was heavily influenced by the cartoonist and guohua (“National Painting”) painter Ye Qianyu, an example of whose work can also be seen in the exhibition (EA1995.274). Gao is particularly well known for his paintings of scenes from Chinese drama following in the tradition of artists such as Guan Liang 关良 (1900-1986).

Guan Liang, Scene from the Peking Opera The Case of the Beheading of Chen Shimei (Zha Mei an 鍘美案), EA1968.74 © the artist’s estate

See for example a painting in the museum’s collection showing the Peking Opera The Case of the Beheading of Chen Shimei (Zha Mei an 鍘美案). This was a court case presided over by Judge Bao, a popular figure in Chinese fiction based on the Song dynasty magistrate Bao Zheng (AD 999-1062). In the painting, to the right, can be seen Chen Shimei who betrayed his wife Qin Xianglian by marrying the emperor’s daughter (the honour of coming first in the imperial examinations having rather gone to his head). At the order of Judge Bao, his faithful servant Zhan Zhao, who can be seen in the centre, executed Chen Shimei and saved the life of Qin Xianglian who Chen had plotted to murder.

The Legend of the White Snake a scene of which can be seen in Gao Made’s painting in the exhibition is one of the most popular dramas in the Peking Opera repertoire, not least because of the extraordinary acrobatic sequences that appear towards the climax of the story. The actor who plays the female lead – the White Snake – rarely leaves the stage during the entire length of the performance and has an extremely demanding role as both a singer and acrobat.

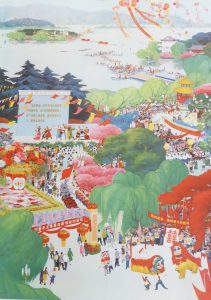

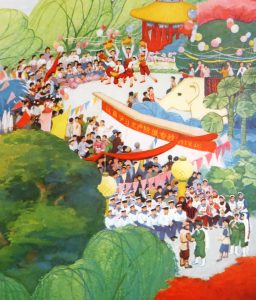

- Xu Ping, West Lake on New Year’s Day (Jieri Xihu 节日西湖), Poster, EA2006.228

- Xu Ping, West Lake on New Year’s Day (Jieri Xihu 节日西湖), Poster (detail), EA2006.228

To place the story of the White Snake into geographical context we will first look at a poster that depicts West Lake in Hangzhou on a festival day in more recent times. In this scene a number of theatrical performances can be seen taking place amongst the thronging crowds. Towards the lower right-hand side of the scene can be seen a performance in miniature of the Model Opera Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy (Zhiqu Weihushan 智取威虎山). Small though it is, it can be identified as the scene from this play in which the huntsman’s daughter Xiao Changbao 小常宝sings a solo aria in the company of the stories hero, a soldier of the People’s Liberation Army. It is interesting to note that the actress who played this role in the 1970 film became well known for her performance as Bai Suzhen, the lead role in “The Legend of the White Snake”.

An outline of the story is as follows:

At the time of the Qingming Festival, the white snake spirit, and her servant the green snake descend into the mortal world in human form as Bai Suzhen and Xiao Qing. On arrival at West Lake, Hangzhou, Bai meets with a young scholar, Xu Xian who offers her his umbrella against the rain. They fall in love, are married, and soon after establish an apothecary shop in Zhenjiang. The Buddhist monk Fa Hai knows of Bai’s otherworldly origins and persuades Xu to give her realgar wine (made from arsenic sulphide), in full knowledge that by doing so she will reveal her true identity. Having drunk the wine she reverts to her original form and Xu Xian promptly dies of fright. This is the scene depicted in the painting, before her actual transformation. In order to bring her husband back to life, Bai Suzhen is compelled to risk her own life to go in search of the antidote, a magic herb, found only at Mount Emei.

This is often performed at the time of the Dragon Boat Festival when realgar wine is traditionally drunk to drive away poisonous creatures such as snakes, centipedes and scorpions. The scene is also known as Stunned by the Transformation at the Dragon Boat Festival (Duanyang jingbian 端陽驚變).

Gao Made, Chun Cao Outwits the Magistrate , 1989, Reyes Gift, EA1995.192 © the artist’s estate

A woman takes centre stage again in a second Peking Opera excerpt illustrated by Gao. This is a scene from Chun Cao Outwits the Magistrate (a.k.a. Chun Cao Braves the Court). In this story, a maidservant Chun Cao, learns that a righteous and morally upright man – typical of the young scholar gentleman of the time – is to be wrongly sentenced to death. She decides to trick the magistrate into believing that the accused is betrothed to her mistress, the prime minister’s daughter, as a ruse to save him. The two eventually marry.

The men in the scene depicted by Gao – four attendants and the magistrate leading at the front – are all examples of the clown role, known as chou 丑in Chinese, and the white make-up applied to the ridges of their noses indicates this to be the case. In the centre is Chun Cao.

New Year’s Print showing characters from the Water Margin, EA2006.3 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

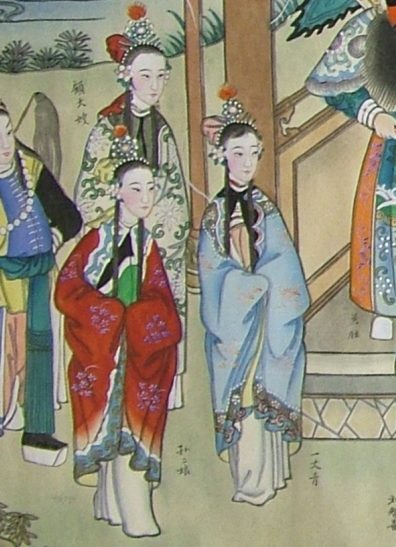

In a popular woodblock print showing a scene from a Peking Opera version of the Ming dynasty novel the Water Margin three women appear amongst the assembled crowd.

Wearing full Peking Opera regalia and seated in the centre of the Hall of Loyalty and Righteousness (in this print a depiction of the typical theatrical stage on which Peking Opera is performed) is the leader of the 108 rebels, Song Jiang, and assembled around him can be seen several other key figures in the story:

Centre stage, out in front, is Li Kui, a fearsome character known as the Black Whirlwind who is the lead character in the Peking Opera scene depicted: Li Kui danao Zhongyitang 李逵大鬧忠義堂 (Li Kui Causes Havoc in the Hall of Loyalty and Righteousness), also known as: Dingjia shan 丁甲山 (Dingjia Mountain); Li Kui fanzui 李逵犯罪 Li Kui Commits an Offense; and Danao zhongyitang 大鬧忠義堂 Havoc in the Hall of Loyalty and Righteousness.

Standing on stage, to the right, is Lin Chong, one of the central figures in the popular Peking Opera Yezhulin (Wild Boar Forest). As with many full-length Peking Operas, Ye Zhulin was originally just a short excerpt from the Water Margin. On the left is Wu Song, whose story covers several chapters in the original novel: from the time when, under the influence of strong alcohol he beats a tiger to death with his bare hands and becomes the hero of the local villagers, to his involvement with the lecherous dealings of Ximen Qing and his own brother’s wife Pan Jinlian, both of whom meet their deaths at his hands for the murder of his brother.

To the left of the print can be seen three women. These are amongst the small number of women bandits that appear in the Ming dynasty novel:

At the back: Gu Dasao顧大嫂, nicknamed “Tigress” (Mu da chong 母大蟲 ), a prolific martial artist. In front, to the right, is Hu Sanniang扈三娘, also known as Yi Zhangqing 一丈青 (as indicated in this print). On the left is Sun Erniang孫二娘 who is nicknamed “Yaksha” (Mu yecha 母夜叉) after the female Buddhist spirit, due to her fierce and wild appearance.

In the Peking Opera Shizipo 十字坡 based on an episode in the book, Sun Erniang and her husband Zhang Qing own a tavern to which they lure travellers, drugging them, slaughtering them, and filling their steamed dumplings with their cooked flesh. Following an encounter with Wu Song (who did not fall for their ruse) and after a fierce fight between them, Wu becomes the sworn brother of Zhang Qing. The married couple later join the bandits at Liangshanbo.

Four matchboxes depicting figures in Peking Opera roles, EA2010.84 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Wu Song can be seen as he appears in the opera Shizipo on one of four matchboxes in the Ashmolean collection. These are just a small sample of a collection of several hundred matchboxes that was accumulated in China in the 1970s and 1980s, and entered the museum’s collection rather more recently. Three more examples show heroes from the Water Margin. The first two, on the left of the picture, show Sagacious Lu and Lin Chong as they appear in the popular opera Yezhulin (Wild Boar Forest). The fourth example shows Qin Ming, the “Fiery Thunderbolt” a brave warrior figure, as indicated by his painted face and long stage beard.

In the Water Margin print, the banner on the left above the heads of the assembled crowd tells us that they are all gathered together in the bandit’s lair – Liangshanbo – in the marshes far from the eyes of the imperial court. The banner on the right: “Root out the Cruel to make way for Peace” (Chubao anliang 除暴安良) is part of the maxim of the bandits at Liangshan, which continues: “Carry out ‘The Way’ for the Sake of Heaven” (Titian xingdao 替天行道).

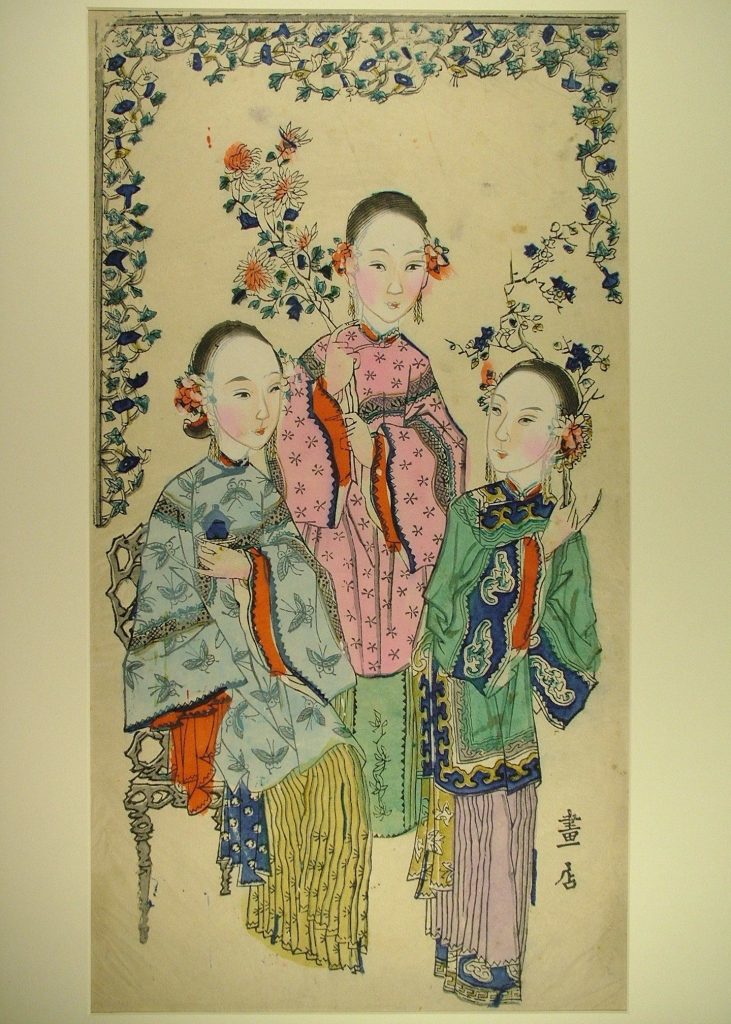

- New Year’s Prints showing women in domestic settings, EA1970.86.a and EA1970.86.a

This depiction of the Water Margin is an example of a New Year’s Picture, a type of popular print that often took Peking opera excerpts as its theme. The New Year’s Picture that appears in the exhibition “A Century of Women in Chinese Art” is rather different as it shows two women in a domestic scene. Despite being different in both theme and appearance these prints both served the same function: to act as auspicious decoration displayed as part of the New Year festivities. A related print again shows three women in a domestic setting. This is replete with symbolism, showing off particularly well the clothes of the young women that are very much of the same period as the silk jacket and skirt on display in the exhibition.

Embroidered Jacket, 20th century (before 1938), EA2015.32

Embroidered Skirt, 20th century (before 1938), EA2015.32

For more on women in martial arts, as seen in the Water Margin, see the next instalment of this blog.

Dr Paul Bevan, Christensen Fellow in Chinese Painting, Ashmolean Museum

11 July 2018 Guided tour of the exhibition with Dr Paul Bevan