In this blog we will be looking at a small number of the exhibits in the current exhibition “A Century of Women in Chinese Art” now on show at the Ashmolean Museum until the 14th of October 2018, with reference to a variety of additional objects in the museum’s collection that it has not been possible to include in the exhibition.

The Ashmolean Museum holds an extensive collection of objects from the Cultural Revolution period (1966-1976). One striking exhibit that appears in the exhibition is a ceramic figurine of a young woman in army uniform washing the floor with mop and pail.

Girl in Army Uniform with Bucket and Mop (1970-1979)

Porcelain figure, with polychrome glazes; wooden mop handle

Jingdezhen, Wade Gift, EA2010.78 © the artist

Throughout the period of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) the porcelain kilns at Jingdezhen, renowned as the imperial kilns since the early Ming dynasty (c.1400), continued to produce fine quality porcelain. Much of the output from this time used the forms and decoration of revolutionary imagery, often depicting Chairman Mao himself, heroes from revolutionary history, and in particular figures from the eight Yangbanxi – often known in English as the “Model Operas”. These revolutionary dramas, ubiquitous during the period and still hugely popular today, originally included five modern Peking Operas, two ballets – Red Detachment of Women and The White Haired Girl – and one symphonic work, the Shajiabang Symphony. Later the symphony was replaced by other theatrical productions. Women play central roles in all of these.

At the time of the Cultural Revolution, images taken from these popular dramas could be found reproduced on all manner of everyday objects, from thermos flasks to teapots, from biscuit tins to matchboxes. One example of the latter in the Ashmolean collection shows an image of the lead female character from The Legend of the Red Lantern (红灯记 Hongdeng ji) (EA2010.229.1). This drama tells the story of Li Tiemei and her role in the communist underground during the War of Resistance against Japan (1937-1945); this conflict, and the civil war that succeeded it, being the most common themes on which these dramas were based.

Matchbox with image of Li Teimei from The Legend of the Red Lantern, Wade Gift, EA2010.229.1 © the artist

Perhaps the best known of the Model Operas is actually a ballet: The Red Detachment of Women (红色娘子军Hongse niangzijun). This tells the story of a young woman who escapes servitude on Hainan Island, one of the last stands of the Nationalists in the Civil War before the People’s Republic of China was established. Wu Qinghua defies the local gentry that have enslaved her, and the Nationalists authorities who prop up the corrupt landowners, and joins the “Red Detachment of Women” to overthrow them.

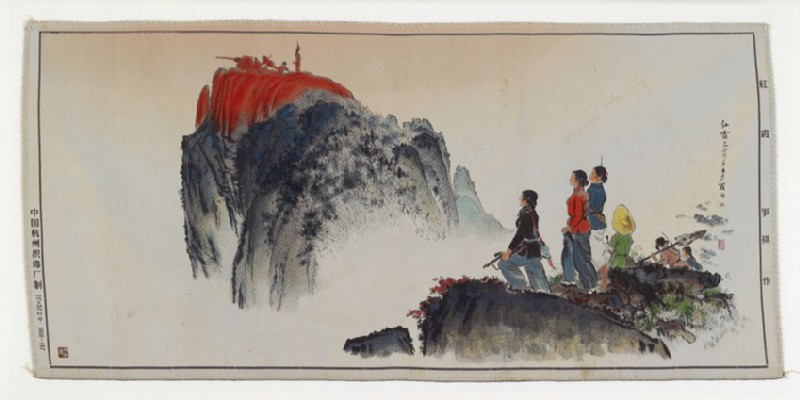

Another example, in which women are represented in their new role as active participants in the military struggle for a socialist society, is on display in the exhibition. This a woven silk picture based on an oil painting by the artist Luo Qi 罗祺 (b.1929) (EA2010.284). The scene depicted shows a group of armed female militia looking up towards the red glow at the mountain top, on which a gun placement can be seen and where the red flag of the People’s Republic of China is flying; the ‘red glow’ of the title alluding to the Chinese Communist Party and to Mao Zedong himself.

Red Glow (1964) after a painting by Luo Qi 罗祺 (b.1929)

Woven silk with applied colour pigments, EA2010.284 © the artist

Luo Qi’s original painting, on which this silk textile is based, was awarded the highest prize when it was displayed in the Fourth National Art Exhibition; the exhibition to celebrate the 15th anniversary of the establishment of the PRC that took place in 1964. This silk example was woven in black and white and colour was later applied by hand, a speciality of the “Hangzhou Picture Weaving Factory” at which it was made.

Figures from The Red Detachment of Women can be seen in two sets of papercuts in the Ashmolean collection (EA2008.37.b). This story was known to all during the period of the Cultural Revolution and was performed across China, adapted to local theatrical forms using a host of different Chinese dialects. The most famous filmed version of the story is the ballet; so famous was it that it later became an inspiration for the American composer John Adam’s modern opera Nixon in China. The ballet version of the Red Detachment of Women was based on a hugely popular feature film that had been released in 1961 and the ballet was followed by a Peking Opera version.

Wu Qinghua from the ballet Red Detachment of Women

Gittings Gift, EA2008.37.b © the artist

For more on Peking Opera, see the next instalment of this blog.

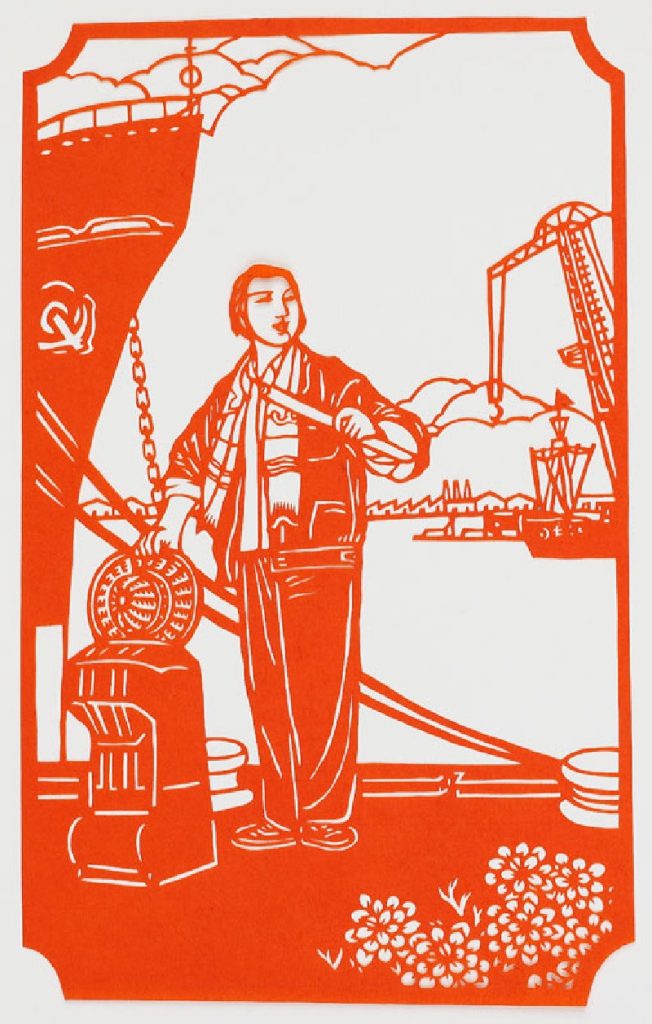

In another set of paper cuts in the museum’s collection can be found an image of a woman dock worker, calling to mind the Model Opera On the Docks (Haigang 海港) (EA2008.34). This revolutionary drama, written by Xie Jin and originally staged in the 1960s, was filmed in 1972 and starred Li Lifang as Fang Haizhen. It tells the story of a team of dock workers loading a cargo of rice to be shipped to Africa, overseen by the heroine Fang Haizhen, local communist party secretary. A counterrevolutionary attempts to sabotage their mission by substituting glass fibre for the rice, but is discovered by Fang. The plot is foiled and the perpetrators brought to justice.

Papercut – Woman Docker

Gittings Gift, EA2008.34.c © the artist

A poster from the museum’s collection shows stars from the Model Operas, (EA2006.261). The main caption reads: ‘Long Live the Triumph of Chairman Mao’s Revolutionary Line of Literature and Art!’ It will be noticed that four of the ten figures depicted are women, although, Li Tiemei, from the Legend of the Red Lantern and Wu Qinghua are not amongst those shown here. In the front row can be seen Xi’er – the White Haired Girl, lead protagonist in the 1966 ballet, based on a story from the 1940s. In the middle row, from right to left, can be seen the female leads from other revolutionary operas: Ke Xiang from Azalea Mountain (Dujuan shan) (1973), Jiang Shuiying from Ode to the Dragon River (Longjiang song) (1972), and, on the left, Fang Haizhen from On the Docks.

Poster – Characters from Revolutionary Operas, EA2006.261 © Shanghai People’s Publishing House

Another type of revolutionary woman altogether, can be seen in the 1971 print “There are Heroes Everywhere” Biandi yingxiong 遍地英雄 by the printmaker Zhang Chaoyang 張朝陽 (b.1945) (EA2007.90). This print, the title of which suggests that revolutionary heroes could be found in all walks of life, shows a harvest scene during the Cultural Revolution, at a time when young educated city dwellers had been sent “Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside” Shangshan xiaxiang 上山下鄉 to be “re-educated” by the local peasantry. The title of the print is taken from the final line of a poem by Chairman Mao, entitled, Dao Shaoshan 到韶山 (To Shaoshan) (1959) – one of many poems written by Mao Zedong – composed on a visit to his hometown after an absence of 32 years.

Zhang Chaoyang 張朝陽, “There are Heroes Everywhere” Biandi yingxiong 遍地英雄 (1970) EA2007.90 © the artist

In 1976, with the death of Mao, which brought the Cultural Revolution to a close, the educated youth slowly began to return to their hometowns. A scenario closely related to this can be seen in the 1977 print prominently shown in the exhibition “Returning after Graduation” Biye guilai 毕业归来 by Li Xiu李秀 (b.1943), an impressive, large multi-block woodcut print using oil-based inks (EA2007.43).

From just a few clues in the detail of this print it can be deduced that the three young people in the picture have returned to their hometown in southwestern China following their graduation in Beijing (note the copy of Beijing Daily in the pocket of the young man). They had certainly been roughing it on their journey, as the number on the side of the train reveals the information that they had been travelling in a “hard seat” carriage, on a long distance sleeper, with no air conditioning; a journey, from the Chinese capital to Kunming in Yunnan, of almost 2,000 miles.

Li Xiu李秀, “Returning after Graduation” Biye guilai 毕业归来 (1977), multi-block woodcut printed with oil-based inks, EA2007.43 © the artist

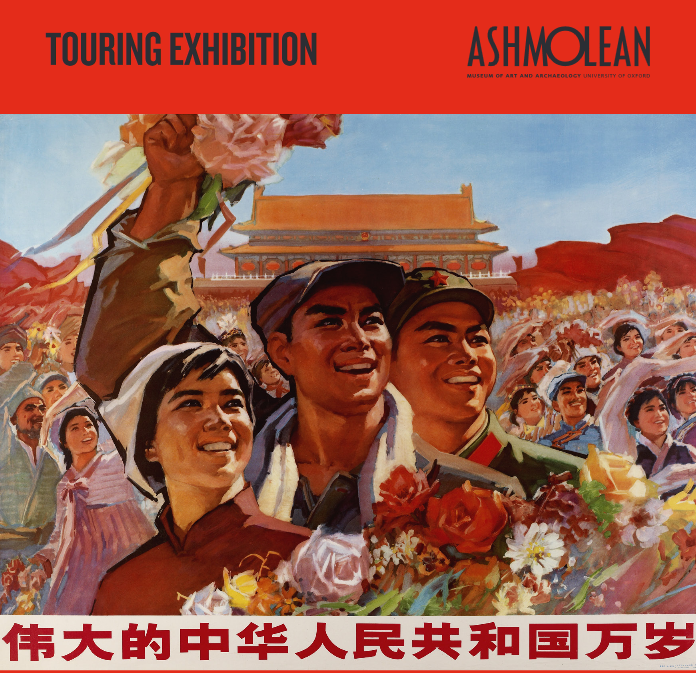

The young lady and the man to her left are dressed in the costume of the Yi, a minority people found in the provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, and Guangxi. The other figures in the print are wearing the uniform of the People’s Liberation Army. This conveys an atmosphere of new found hope and freedom, having been made in the year immediately following the end of the Cultural Revolution. Following its appearance, this print quickly became one of the most published in China. It is often regarded as a depiction of the artist’s own experience, Li Xiu herself being a member of the Yi minority. The smiling faces, beaming with unbridled delight, show traces of the distinctive style that was often seen in the art of that period, for example, with the figurine of the girl with a mop and in the faces on the poster depicting the figures from the Model Operas. On another poster in the Ashmolean collection such delighted expressions can be seen again. Here the caption reads: “Long Live the Great People’s Republic of China”

Poster – “Long Live the Great People’s Republic of China”, based on an original painting by Jiao Huanzhi (1928-1982) and Sun Quan (active 1974), EA2006.267 © People’s Fine Arts Publishing House

The Ashmolean Museum is currently offering a travelling exhibition on the theme of the Cultural Revolution to venues round the country. See leaflet here.

Events linked to the “A Century of Women in Chinese Art” exhibition:

16 June 2018 Women in Chinese Art Symposium

11 July 2018 Guided tour of the exhibition with Dr Paul Bevan

Dr Paul Bevan, Christensen Fellow in Chinese Painting, Ashmolean Museum