The genre of Japanese woodblock prints known as surimono is characterised by the harmonious combination of poetry and image. Surimono were produced specifically for private use, not for sale in the market, to exchange as gifts on special occasions, particularly for the New Year, among the members of poetry clubs during the late eighteenth and the mid-nineteenth centuries. During this period the poems mainly composed in the clubs were called kyōka (literally crazy verse), or humorous verse, which gained dramatic popularity among small numbers of the samurai class and townspeople, including wealthy merchants in Edo (modern Tokyo). From the 1780s, kyōka poets began commissioning artists to illustrate their poems. The artists commissioned to supply pictures for surimono mostly belonged to the ukiyo-e school. Leading surimono designers included Kitagawa Utamaro, Katsushika Hokusai and his pupils (Hokkei, Gakutei and Shinsai), Kubo Shunman and Utagawa Toyokuni. The surimono produced by the collaboration of kyōka poets and artists are grouped as kyōka surimono. The surimono on display in the exhibition ‘Plum Blossom & Green Willow’ are mainly kyōka surimono, with a few haiku surimono that include haiku rather than kyōka poems.

The combination of poetry and image seen in surimono is, in fact, part of a long Japanese tradition of unifying literature and art, typically seen in painted hand-scrolls of classical stories, such as the tenth-century Tales of Ise and the twelfth-century Tale of Genji (including text with poems alongside the pictures). The Chinese style hanging scrolls of the eighteenth century, known as Nan-ga, also often include poetic inscriptions in calligraphy. Poetry has long been inextricably linked with art in Japan and has always played an important role in Japanese culture and aesthetics. There is a famous phrase by the court poet Ki no Tsurayuki in the preface to the Kokin wakashū (Collection of Ancient and Modern Japanese Poetry), an early imperial anthology of c. 914 : ‘yamato uta wa hito no kokoro o tane to shite yorozu no koto no ha tozo narerikeri’ (‘Japanese poetry takes as its seed the human heart’). In other words, men and women speak of things they hear and see, giving words to the feelings in their hearts.

Poetry has also traditionally been seen as more than simply a form of personal expression. Reciting Japanese poems at religious ceremonies or at public banquets in ancient times enhanced the solemnity of the receptions, pleased the gods and Buddha, and also united the participants spiritually, having an effect akin to chanting mantra. In the seventh and eighth centuries, Japanese poems were often sung in ritualistic ceremonies, accompanied by the wa-gon (Japanese 5 or 6 stringed instrument), which was played as means to commune with the gods and also to enhance communication between individuals.

Waka, the Japanese classical poetry form consisting of 31 syllables (5/7/5/7/7) that stemmed from these ancient Japanese poems, developed into various waka poetry styles from the mid-eighth century. Waka poems were exchanged personally among high-ranking courtiers and recited on social occasions such as uta-kai (poetry gatherings) or uta-awase (poetry competitions). Kyōka poetry in surimono can be regarded as the descendant of this literary tradition, using exactly the same structure and poetic techniques as waka. However, kyōka dispensed with many of waka’s formal constraints of style and theme, rather showing its witty, sometime sarcastic wordplay, thus being called ‘crazy’ or ‘humorous’ verse.

The ritualistic aspect of reciting poems can be likened with exchanging surimono among kyōka poets of poetry clubs at the New Year or on special occasions such as the celebration of an age milestone. The poems composed for New Year’s surimono often conveyed wishful thoughts of happiness and prayers to the gods, particularly prayers to Toshigami, a god worshipped at the beginning of the New Year, and to whom poems were dedicated with accompanying pictures. New Year’s surimono were known as saitan surimono (surimono for New Year’s Day) or shunkyō kyōka surimono (surimono for celebrating spring). The New Year was the most important event in the Japanese festival calendar, marking the rebirth of nature in springtime.

Most kyōka surimono were composed to commemorate New Year’s poetry gatherings. The subjects of the poems and images on surimono are varied, with the most conspicuous themes being still-life subjects, Kabuki actors, zodiac animals, legends and literature, among others. What was common to all New Year’s surimono was that they invariably carried auspicious imagery that conveyed messages of vigour, happiness, longevity, beauty and wealth. Both those sending and receiving surimono would be suffused with the pleasure of anticipation of positive things to come. The sense of anticipating auspicious things for the New Year took the form of ritualistic prayers and events known as yoshuku. These consisted of celebrating in advance the thing that was wished for and performing actions designed to imagine the actual realisation of that thing.

The poems and images on surimono often performed a similar function. Thus the tobacco pouch in the surimono ‘Pipe case and tobacco pouch with a netsuke and chain’ represents fullness and happiness because it is fully packed with tobacco.

Pipe case and tobacco pouch with hyogo-gusari chain and netsuke

Kikukawa Eishin (active c. 1804-30) 菊川英信

Artist’s signature: Hōrai Eishin ga 蓬莱英信画

Artist’s seal: Ei 英

c. 1820s

Colour woodblock print with metallic pigments and embossing

12.6 x 17.3 cm, kokonotsugiriban format

Presented by Mrs E.M. Allan and Mr and Mrs H.N. Spalding from the Herbert H. Jennings Collection, EAX.4615

This surimono represents a celebrative and happy New Year theme. The poem reads: ‘Laughing at the stitches of a spring pouch fully packed with tobacco – what a joyful time!’ ‘Spring pouch’ (haru-bukuro in Japanese) is the key word to link the kyōka poem with the picture, and to offer various interpretations of the surimono. ‘Harubukuro’ was a type of pouch made in the New Year by a young woman wishing for the pouch – generally a drawstring purse – to be filled with happiness in the year ahead. The playful poem by the kyōka poet Uramichi Chikaki (meaning ‘back street shortcut’) has turned the woman’s spring pouch into a man’s tobacco case fully packed with tobacco. The designer, Eishin, an ukiyo-e artist, has depicted a tobacco case with a braided metal chain (hyōgo-gusari) embellished with a boar’s tusk netsuke and fur pompom. The green pipe case that accompanies the tobacco pouch is sewn with irregular stitches that reference the poem. The word ‘haru’ is a pun, or ‘kakekotoba’ in Japanese, meaning both ‘spring’ and ‘being full’. The pipe case is empty and it is possible that Eishin’s design incorporates a risqué interpretation of a young woman’s ‘full pouch’.

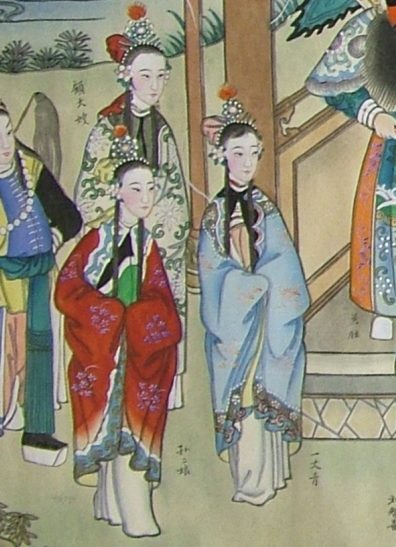

Surimono sometimes alluded to classical themes of the past in a form of gentle parody known as mitate. In mitate, esteemed historical, religious or literary personalities were depicted as contemporary figures such as courtesans or actors. For example, in the surimono below, the Chinese immortal Rogō is portrayed as a courtesan.

The Immortal Rogō

Series title: The biographies of immortals parodied by courtesans: a set of seven (Keisei mitate ressenden: nanaban no uchi 傾城見立列仙伝 七番の内)

Probably commissioned by the Tsurunoya poetry group

Yashima Gakutei (c. 1786 – 1855) 屋島岳亭

Artist’s signature: Tōto Gakutei 東都 岳亭

Artist’s seal: Sadaoka 定岡

1827-1834

Colour woodblock print with metallic pigments,

20.8 x 18.5 cm, shikishiban format

Presented by Mrs E.M. Allan and Mr and Mrs H.N. Spalding from the Herbert H. Jennings Collection, EAX.4561

This surimono is one of seven prints in a series designed by Yashima Gakutei. The series likens famous courtesans to venerated immortals of the Chinese Daoist tradition, which is included in the category of legendary subject. The courtesan depicted here is the allusion to the immortal Rogō (Lu Ao in Chinese), who is often depicted riding on the back of a turtle. The designer of the surimono, Yashima Gakutei, has depicted a courtesan as if she were seated on the back of a long-tailed turtle embroidered on the bottom of her splendid kimono – the long-tailed turtle is an auspicious symbol of longevity. Gakutei seems to have been well acquainted with the subject and has extended the turtle imagery by depicting a tortoiseshell pattern on the courtesan’s obi (sash) and on the upper part of purple her purple kimono. This tortoiseshell pattern was typically found on the armour of the deity Bishamonten, one of the Seven Gods of Good Fortune and the Buddhist guardian of the north – one of the four directions represented by a turtle.

The turtle is also associated with an ancient East Asian practice of divination (uranai), in which the cracks that appeared on the surface of a heated turtle shell would foretell future events. In the poem, the phrase ‘kame no urakata uramasa ni ‘ [the fortune (urakata) predicted by the turtle (kame) happened as predicted (uramasa)] has a close association with the theme of Rogō riding on the back of a turtle. The background of the surimono is decorated with a pattern of cranes (tsuru), probably associated with the emblem of the Tsurunoya poetry group, who commissioned the surimono. The combination of crane and turtle is a most favoured motif as representing longevity (according to legend the crane lives up to a thousand years and turtle up to 10,000 years).

‘Still life’ was a popular subject for surimono, in contrast to commercial ukiyo-e woodblock prints which mostly depict the beauties of the pleasure quarters and popular Kabuki actors. The still-life depicted on the surimono ‘A vase with plum twigs and a crab on a court hat’ stirs your imagination of how these objects are related each other and what kind of narration could be unravelled. Only by reading the poems can the reader begin to understand the meaning of the picture.

A vase with plum twigs and a crab on a court hat

Rintei Yūshin (act. 1780s – 1820s) 林亭雄辰

Artist’s signature: Rintei

Probably 1825 (Year of the Rooster)

Colour woodblock print

16.5 x 20.4cm, kokonotsugiriban format

Purchased with the assistance of the Story Fund, EA2017.35

This surimono is a still life that shows a blue-and white vase containing twigs of plum blossom and a crab on an eboshi, a type of lacquered black hat worn by high-ranking nobles. These objects are laid on a chintz fabric with motif in red and green, all of which is presented in a diagonal bird’s-eye view, lacking a sense of three-dimensional perspective. The vase looks as if it is floating in the air. The theme of this surimono is puzzling – the meaning of the picture only becomes clear once the poems have been fully appreciated. The key to unlocking the surimono lies in the place name ‘Akama’, found in the second and fifth verses. Akama is also known as Akamaga-ga-seki (modern Shimonoseki City of Yamaguchi Prefecture) and is the place where the Battle of Dan-no-ura took place in 1185, at which the Heike clan suffered a final defeat and was vanquished. Consequently the opposing Genji clan took the power of controlling the country. This battle marked a cultural and political turning point in Japanese history: Japan was to be ruled by Shoguns and warriors instead of Emperors and aristocrats.

At the site of the battle at Akama-ga-seki is found a type of crab whose shell bears a pattern resembling a fierce human face, like the crab depicted in the surimono. These crabs are called the Heike-gani (Heike crabs). It is locally believed that these crabs are reincarnations of the Heike warriors defeated at the Battle of Dan-no-ura as told in The Tale of the Heike. The black eboshi court hat on which the Heike-gani is placed represents the Heike family, who gained power by matrimonial links to the imperial court. The surimono was produced probably in the year of the Rooster, which can be surmised from the inscription around the base of the vase indicating of the date of production, the Bunsei era (1818-30).

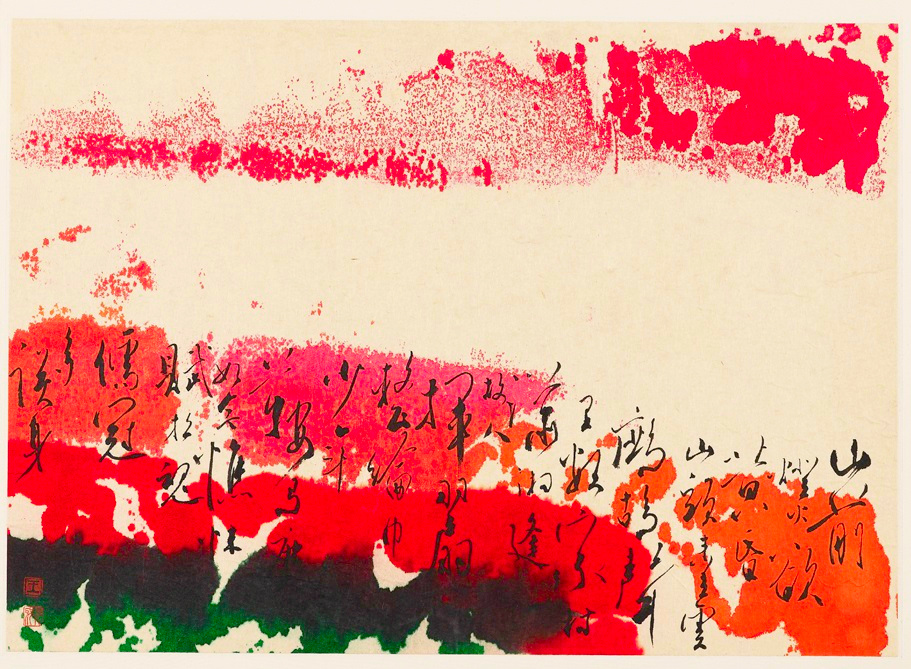

The beautifully designed surimono below was produced for the poet who commissioned the surimono, to celebrate the special occasion of his early old age (shorō). It was commissioned with wishful thoughts of longevity.

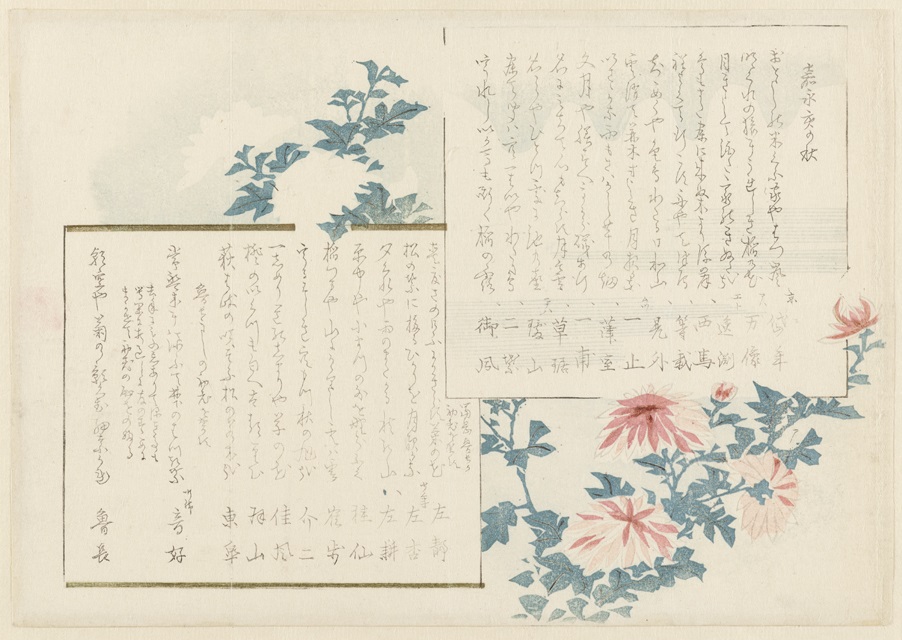

Two sheets of haiku poems with chrysanthemums

Commissioned by the poet Tomioka Rochō

Artist unknown

1851

Colour woodblock print with embossing

19.5 x 28cm, chūban format

Acquired 1979, EA1979.21

This surimono consists of two sheets of haiku poems decorated with red and white chrysanthemums that are depicted using an embossing technique. The haiku poetry form was born when the starting verse (hokku) of the linked poems known as renga became independent. Renga itself developed from 31-syllable waka (5/7/5/7/7) and was a collaborative poetry genre in which different poets contributed the upper stanza (5/7/5) and lower stanza (7/7) of waka in turn. Haiku ( the upper stanza) consist of 17 syllables in a 5/7/5 meter. Nature plays the most important role in haiku, and a seasonal word (kigo) must be included in each haiku.

The inscription at the beginning of the left sheet declares that the poet ‘ Tomioka Rochō celebrates his early old age’, known as ‘shorō’, and indicates that the poems on the surimono were composed to celebrate Rochō’s ‘ga no iwai’, a custom commemorating one’s longevity at significant milestones, the first celebration of old age on his 41st birthday. This custom continues in modern times in Japan, but nowadays the first celebration of this kind is at the age of 60, with an event known as ‘kanreki’, returning to the year you were born in a sexagenary cycle.

The poems on the two poetry sheets depicted are composed by poets gathered from various prefectures, including modern Tokyo, Kyoto, Tokushima, Chiba and Aomori Prefectures, to contribute to Rochō’s milestone celebration, and also to wish for blessing of longevity. The poems are filled with autumnal imagery (kigo seasonal words), including references to autumn plants, geese, and numerous poetic terms for the moon in autumn, as the following examples illustrate.

Sōkyo of Mutsu Province: ‘Worthy of the fame, the autumn full moon makes its presence known’

Isshi, also of Mutsu Province: ‘The clouds have cleared – the cool shade of roadside trees on a moonlit night’

The young man Sakyō: ‘On a moonlit night, the reflection of moonlight on pine needles’

Tomioka Rochō’s own poem, the last on the left-hand sheet, alludes to his own old age: ‘I scoop the reflection of chrysanthemums in the narrow stream’, conveying the sense of leaving his mark on nothing, echoing the transience of nature.

Kiyoko Hanaoka

Last Chance to see the Exhibition

PLUM BLOSSOM AND GREEN WILLOW: SURIMONO POETRY PRINTS

on view until Sunday 17 Mar 2019

Gallery 29 | Admission Free

A catalogue of the exhibition is available at the Ashmolean Museum shop.