As it happens with his creative etymologies, Douce’s explanations of particular details taken from the images that he collected are sometimes as difficult to believe as one of Munchausen’s tales. On 1 February 1801, Douce sent the following note to George Ellis, probably in response to a query regarding 15thC-bathing etiquette:

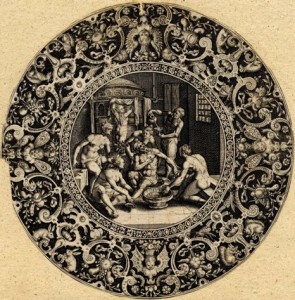

Not only women bathed together, but husbands & wives, lovers and their mistresses used the bath in common. The old fabliaux & romances abound with instances of this practice […]. Promiscuous bathing is likewise exemplified in some of the early specimens of engraving, from which it also appears that women attended men to the bath for the purpose of rubbing, drying, &c.

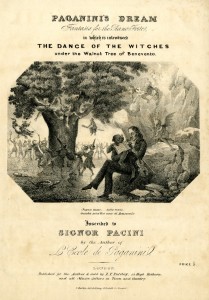

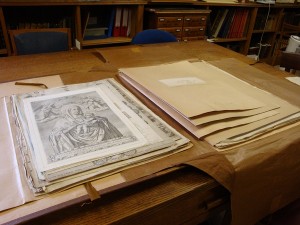

The image above can be found in one of Douce’s folders, labelled ‘Sweating & Bathing Rooms’. It provides an example of how Douce used his collection as a visual encyclopaedia and as a source of information on all aspects of everyday life in the past. As further proof of his account of early modern bathing arrangements, Douce describes another image from his repository:

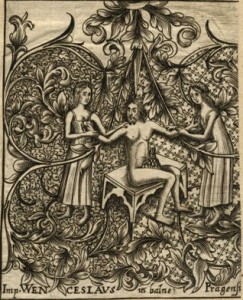

The emperor & King of Bohemia Wenceslas who died in 1418, was remarkably attached to the bathing girl who attended him during his captivity. In a finely illuminated bible written at his instance & still preserved in the Imperial library at Vienna, this woman is represented several times. In one painting, she stands by the emperor who is sitting apparently in the stocks, her arms & legs naked, in one hand a bathing tub, in the other a bundle of green boughs formerly used in Bohemia & perhaps elsewhere, in the baths, to cover the nudities; it was called Badenquast. On account of this girl Wenceslas is said to have bestowed many privileges & inmunities on the owners of the Baths at Baden.

The bathing girl, the naked emperor and the bundle of green boughs are all duly represented in this etching from Douce’s collection:

Are Douce’s Bohemian green boughs a regional version of the more ordinary fig leaves? Were they indeed a fashionable bath accessory? The answer might be hidden somewhere in Peter Lambeck’s notes to his catalogue of the Imperial Library mentioned by Douce. No more green boughs appear among the rest of the images kept in his folders. What matters, however, is how these prints and drawings evince the wonderful oddity of the ‘everydayness’, so central to Douce’s antiquarian pursuits.