In the evening of 26 September 1830, Douce was reading Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe. Scott was a friend of Douce: in 1804, he had sent him a copy of his edition of the medieval romance Sir Tristrem (now in the Bodleian). In a letter to Rev. Polwhele, Scott explained that he had been able to consult ‘two fragments of a metrical history of Sir Tristrem […] in the Romance language’ belonging to Douce when preparing his own manuscript.

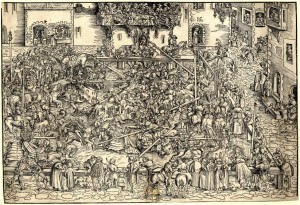

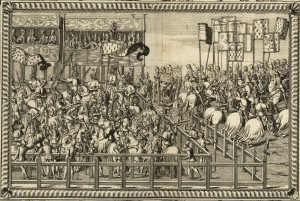

In his book of Coincidences, Douce wrote: ‘I was accustomed in my evening readings to have a portfolio of unsorted prints before me’. The print he took up ‘at random’ just when he was leafing through Scott’s description of the tournament in Ivanhoe was a woodcut of the same subject by Lucas Cranach; the three prints produced by Cranach in connection with the celebrations at Wittenberg in 1508, as well as this tournament in a town square, can be found among Douce’s prints in the Ashmolean:

This work by Cranach is full of life, dynamism, and anecdotal detail, but I always think of Ivanhoe in glorious technicolour -maybe because the first copy of the book I owned as a teenager was a Spanish edition whose cover reproduced a still from the 1952 film adaptation:

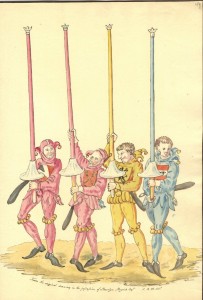

Excitingly, and long before this Hollywood take on Scott’s novel, Douce’s friend Samuel Rush Meyrick (1783-1848) had a similar colourful view of what a tournament should look like. Among Douce’s prints, there are four lively watercolours signed by Meyrick and supposedly based on some original drawings owned by his son, Llewelyn. The image below shows four jesters wearing brightly coloured costumes who could have been part of the ‘gay and glittering procession’ described by Scott at the beginning of the tournament scene:

The four grinning men carry not only the arms of the knights they serve, but also four lances very similar to those depicted by Douce in a sketch kept in the same portfolio:

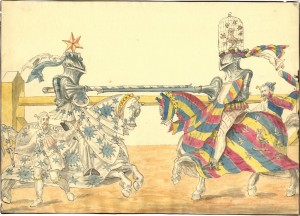

The way the lances were used is illustrated by another of Meyrick’s wonderful drawings, showing two horsemen starting ‘out against each other at full gallop’:

The caged owl attached to the helmet is surely the best heraldic device ever. The original drawings must have been very similar to those in René d’Anjou’s Livre des Tournois (c. 1488-1489). Douce owned a few mid-eighteenth-century prints by Gerard van der Gucht after the scenes of tournaments depicted in the Livre:

These images were produced much later than the episodes described in Ivanhoe, but there is another print among Douce’s which made me think of the misfortunes of Scott’s ‘black-eyed Rebecca’. Although I have not been able to establish what the subject is, an annotation in pencil explains that this ‘Moorish battle piece’ is based on an ‘Arabian painting’ in the Alhambra:

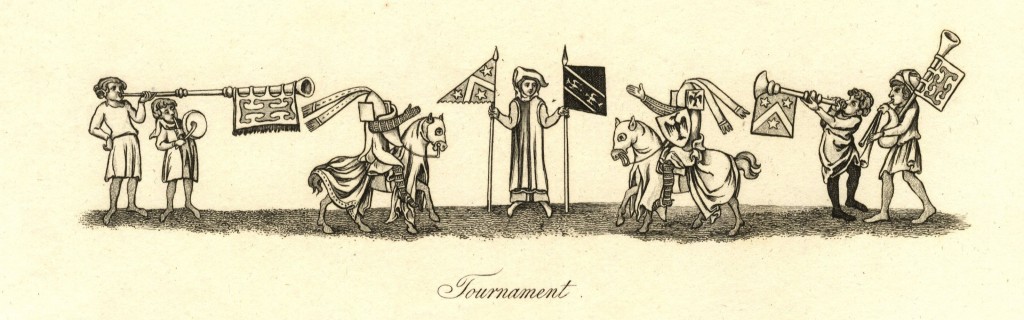

Scott might have also been able to find information on jousting equipment and etiquette in Joseph Strutt’s Sports and Pastimes of the People of England, where the start of the proceedings is thus illustrated: